When we saw indications last August that there could be a late summer wave of COVID-19 cases, those indications were primarily a matter of case count and/or hospitalization tracking. But as research continued, wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) began proving to be a more thorough way of tracking the virus, enabling the detection of asymptomatic and other unreported cases.

Given that, today’s question is whether WBE can be just as instrumental in tracking the current H5N1 avian flu in humans. Two preprint Texas studies have claimed to have found H5N1 in wastewater samples, with the WastewaterSCAN research by Stanford and Emory universities finding the virus present at detectable levels in three sites as early as February 25. In the other study from Baylor and University of Texas, WBE researchers in Texas found that in 9 of 10 cities for which the wastewater was sampled, avian flu virus was found – sometimes at high levels. However, the source of the H5N1 was not clear in either study, though one researcher noted that the evidence points toward animals, “because the researchers didn’t see any mutations with known links to human adaptation.”

While CDC is also using wastewater technology for virus detection, its use to detect human H5N1 is just as unclear. The center’s avian flu monitoring webpage states that “CDC is monitoring wastewater data for any evidence of unusual increases, and influenza wastewater data will be shared soon.” However, the statement seems to be purposely vague with the use of generic influenza, as further down the page, it states, “Current wastewater testing detects but does not distinguish influenza A (H5N1) virus from other influenza A virus subtypes.” How CDC testing differs from Texas testing is unknown, but the discrepancy is likely an answer to those “blasting” CDC over its lack of specific H5N1 wastewater testing.

While there continues to be inconsistencies in the applicability of wastewater testing for human H5N1, the reported results of the university studies, the viability of WBE for detection of COVID, and CDC’s continued focus on the testing indicate that wastewater monitoring is viable for detection of zoonotic viruses. As TAG has been doing for a vast range of infectious diseases, we will keep any eye on this as well, to keep our readers updated on the evolution of the technology and its anticipated eventual ability to separate and independently track human and animal H5N1.

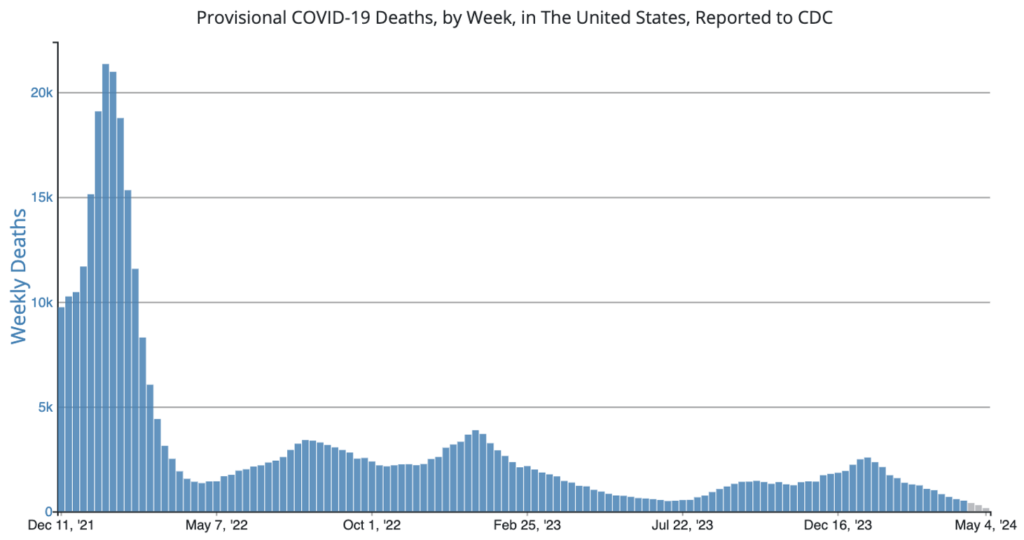

COVID Risk Matrix:

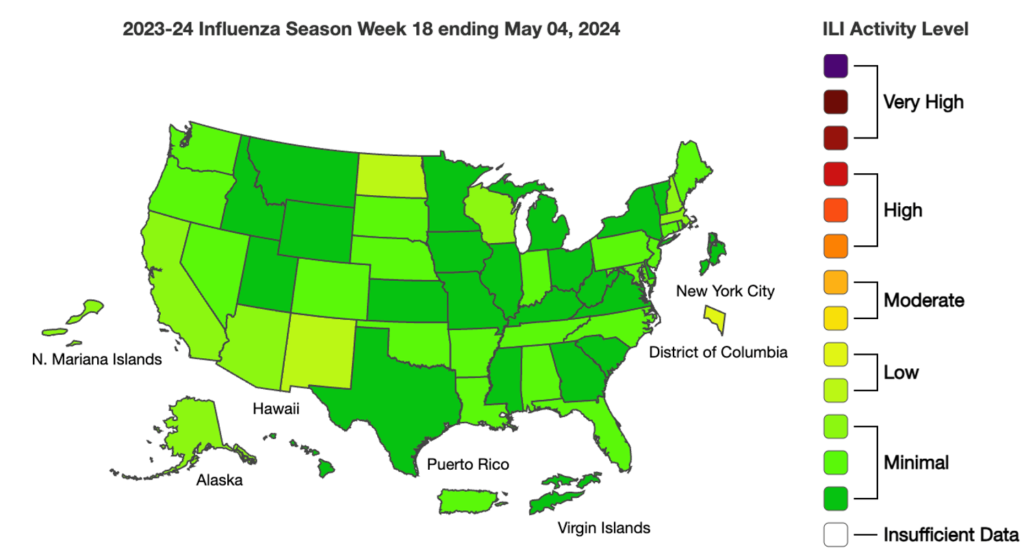

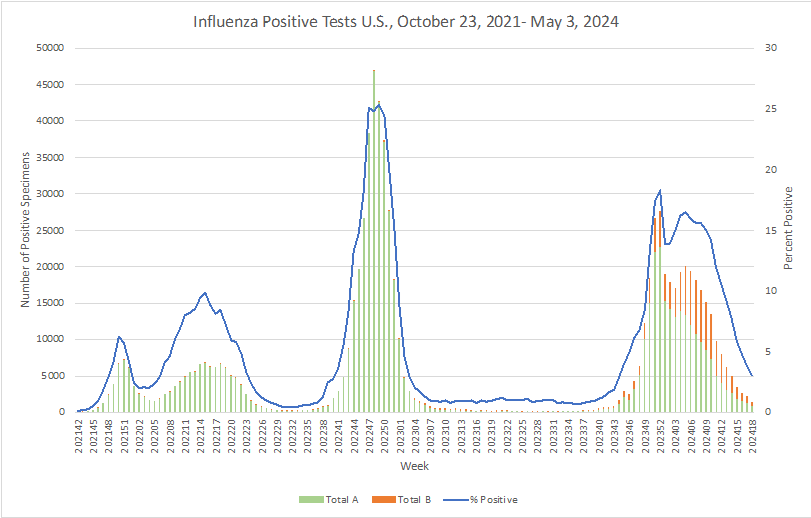

Influenza:

- Researchers in Texas have discovered H5N1 avian flu virus in wastewater samples from nine out of ten cities studied, with concentrations sometimes matching those of seasonal flu. This finding, reported in a preprint by Baylor College of Medicine and University of Texas Health Science Center scientists, highlights wastewater sampling as a crucial surveillance tool. Meanwhile, the CDC has initiated ferret experiments to study H5N1 transmission, following exposure incidents involving over 260 people, with no new human cases confirmed beyond an initial conjunctivitis case in a dairy worker.

- This week the CDC launched their new influenza A wastewater tracker, part of its surveillance for H5N1 avian influenza, as three states reported more detections in dairy herds.

- Scotland has reported its fifth case of classical bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or mad cow disease, since 2014. The disease was detected in a 7.5-year-old cow from a farm in Ayrshire that did not enter the food chain. The United Kingdom’s Animal and Plant Health Agency is conducting an epidemiological investigation to determine the cause of the infection. Meanwhile, as a precaution, the cow’s cohorts and offspring born in the last two years will be humanely culled and tested for BSE.

- A new observational study suggests that interactions with sex workers in bars may be fueling the rapid spread of a virulent new lineage of mpox in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This lineage, known as clade 1, has been found to be more deadly than the clade 2 virus that has been spreading globally since 2022. The research, which involved 371 hospitalized patients in the Kamituga health zone, found that the majority of infections were linked to visits to bars for professional sexual interactions. The study also noted serious outcomes including four deaths and significant fetal loss among pregnant women.

- A study in the *Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report* reveals a significant rise in malaria cases among individuals arriving in three southern US border cities, with a notable increase in severe cases in 2023 compared to 2022. Conducted by the CDC and local health departments, the study found that 68 malaria cases were reported in Pima, Arizona; San Diego, California; and El Paso, Texas—up from 28 in the previous year. The majority of these cases (72%) were among other newly arrived migrants, predominantly those who had traveled through countries with endemic malaria. With nearly a third of the patients experiencing severe illness, the report emphasizes the importance of enhanced outreach and education on malaria for both healthcare providers and new arrivals in the affected areas.

- The FDA advised consumers in Tips to Stay Safe in the Sun: From Sunscreen to Sunglasses that sun safety is always in season. Although all sunscreens help protect people from sunburn, only broad-spectrum sunscreens with a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 15, when used as directed with other sun protection measures, help protect us from skin cancer and early skin aging caused by the sun. The FDA continues to evaluate sunscreen products to ensure that their active ingredients are safe and effective.